Bedford and Bowery, May 2018

MTA Reveals Plans For Williamsburg Bridge Trains at L-pocalypse Town Hall

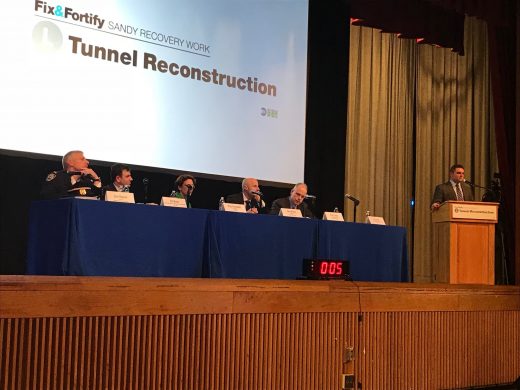

Last night’s Brooklyn town hall about the L train shutdown drew a smaller and generally more supportive crowd than last week’s contentious meeting in the West Village, but some sparring with city officials still revealed a lack of trust in the MTA and DOT on both sides of the East River.

Whereas the Manhattan meeting started with a question about police enforcement against cyclists, the Brooklyn town hall began with a question asking why the planned Grand Street bike lane was only going to be protected on one side of the street. Attendees also repeatedly asked for a 24/7 busway on 14th Street and the Williamsburg Bridge, as opposed to the current plan to run bus-only lanes only during “peak hours.”

The push for a 24/7 busway got an endorsement from an unlikely source, as Blair Bertaccii, a 14th Street resident who showed up to the meeting, asked for that and for the 13th Street bike lane to be permanent. “You have a lot of friends in Williamsburg,” Trottenberg told Bertaccii.

Unlike his neighbors at the meeting last week, Bertaccii told Bedford + Bowery he thought the DOT and MTA outreach effort has been good, and voiced support for commuters and cyclists that was absent at the last meeting. “I’ve heard those people before at other meetings. I think cycling is becoming more and more popular, and once the lanes are put in, hopefully they’ll find it’s not the danger or impediment they believe it’s going to be and that it’s actually a useful piece of infrastructure to have on a street,” he said.

The “peak hours” for the busway are yet to be determined, according to DOT chair Polly Trottenberg and NYCTA president Andy Byford. Before the meeting, Trottenberg told reporters that “we said we would do these two town halls and then the two agencies are going to come back together and take a final look of what makes sense in terms of hours.”

Sone at the meeting were frustrated that, less than a year from the suspension of service, there were still missing specifics from the plan, though the gathered officials did their best to fill in some gaps. Byford said that “no one would be charged an extra fare” while moving between trains, buses and ferries. We also now know that 10 M trains and 14 J trains will be running over the Williamsburg Bridge per hour, after one attendee pushed both Byford and the NYCTA’s Peter Cafiero to tell her exactly how many.

But while the meeting spent time in the weeds of exactly how the city was going to move a quarter of a million L train riders every day, it wasn’t without its somewhat strange theatrics. Byford had a back-and-forth with an attendee who insisted the city study the feasibility of building two more tunnels instead of fixing the existing ones.

A pair of men dressed in suits did an awards show bit announcing the MTA as the winner of “the worst transit system in the entire world,” tried to present the panel with a trophy (they did not accept it) and were roundly booed by the audience the entire time.

Here, Byford, who has treated the challenge of being president of the NYCTA with a cheerful demeanor of a band director ready to turn around an underachieving high school marching band, finally seemed to crack a little bit. While admitting there were problems with the train service, he told the men that the “50,000 fabulous employees of the MTA do their damndest to keep service going, and they’re miracle workers, actually.” Later in the night, Byford again defended the agency, saying “a lot of other cities would love this transit system, even with all its faults.”

And while the Brooklyn meeting had its own version of the attendees in the West Village who wouldn’t trust the MTA’s L train ridership numbers, the crowd seemed ready to give higher marks to the city for their efforts. “Government only works best if it’s a two-way street of trust and communication,” attendee Katy Burgio told Bedford + Bowery. “So the fact that people are coming to these and other meetings they’ve held about the shutdown is good. It’s not easy to mobilize a plan of work like this for any agency or city, particularly New York but they’re trying to do their best.”